Since the end of February, Assistant Professor Faculty Fellow of Sociology Miao Jia has been studying how members of China’s unique network of neighborhood committees (juweihui in Chinese) and residents working as volunteers came together to help each other through some of the mental health challenges of Wuhan’s 70-day COVID-19 lockdown.

With her colleagues from Wuhan and Hong Kong, Miao who began the study while still a faculty member of the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology, recruited volunteers who surveyed some 4,000 residents across Wuhan. They found that the trust and support between Wuhan neighbors - the “social cohesion” - were essential to blunting the mental health impact of the COVID-19 outbreak. Their findings were published in the September issue of Chinese Sociology Review.

Here, Miao, who joined NYU Shanghai this fall and is also a member of NYU Shanghai’s newly-launched Center for Applied Social and Economic Research (CASER), shares the unforgettable human stories behind the study. The project, she says, was one of the most academically and spiritually rewarding of her career so far.

How did you decide to conduct this study?

My colleagues and I have long been studying the neighborhood effects on residents in Chinese cities including Shanghai, Shenzhen, and Hong Kong and we always wanted to extend our research to Central China. Coincidentally, when the first confirmed case of COVID-19 was reported in the news media, I was in Wuhan with my colleagues launching a collaboration with Huazhong University of Science and Technology. That was the last day of 2019, and none of us would have guessed that things would get worse so fast and this city of over 11 million people would be locked down in less than a month’s time.

Amid the world’s skepticism towards the lockdown policy, we felt obliged as sociology researchers to look into people’s lives and their mental status under this special situation. Once the physical connection to the outside world was cut, everyone needed to rely on social infrastructure, various types of organizations within the neighborhood such as residents’ committees and volunteer groups, for necessary goods and social interactions. This was a huge challenge for these public service organizations, and we really wanted to look into how they worked it out and influenced people.

How many people did you survey and how did you reach out to them?

We noticed that soon after the lockdown was announced, studies on Wuhan society and residents began appearing on social media. But many of them didn’t have representative samples, so their results were questionable. We adopted a more reasonable sampling method, which was to recruit some participants and train them to reach out to people of different genders, ages, education levels and socioeconomic status.

The study was launched around one month after the lockdown. We surprisingly received over 150 responses within just three days of our posting the recruitment ad. Every applicant was eager to help us, even though many of them were busy with their volunteer work. We finally got 149 faculty and students from universities all over Wuhan to be the first group of participants and collected over 4,000 surveys from adults living in 943 separate neighborhoods. I was moved by the many participants who asked us to donate their pay to those in need. We were all exhausted in those days working around the clock and facing depressing news, but they were still trying every way to help others.

What role did neighborhoods play in Wuhan’s measures to fight against the pandemic?

China’s urban neighborhoods are managed by residents’ committees. To better meet residents’ varied needs, neighborhoods are further segmented into smaller grids, and each grid is assigned a staff member. Based on such a structure, government policies are more easily enacted on a grassroots level.

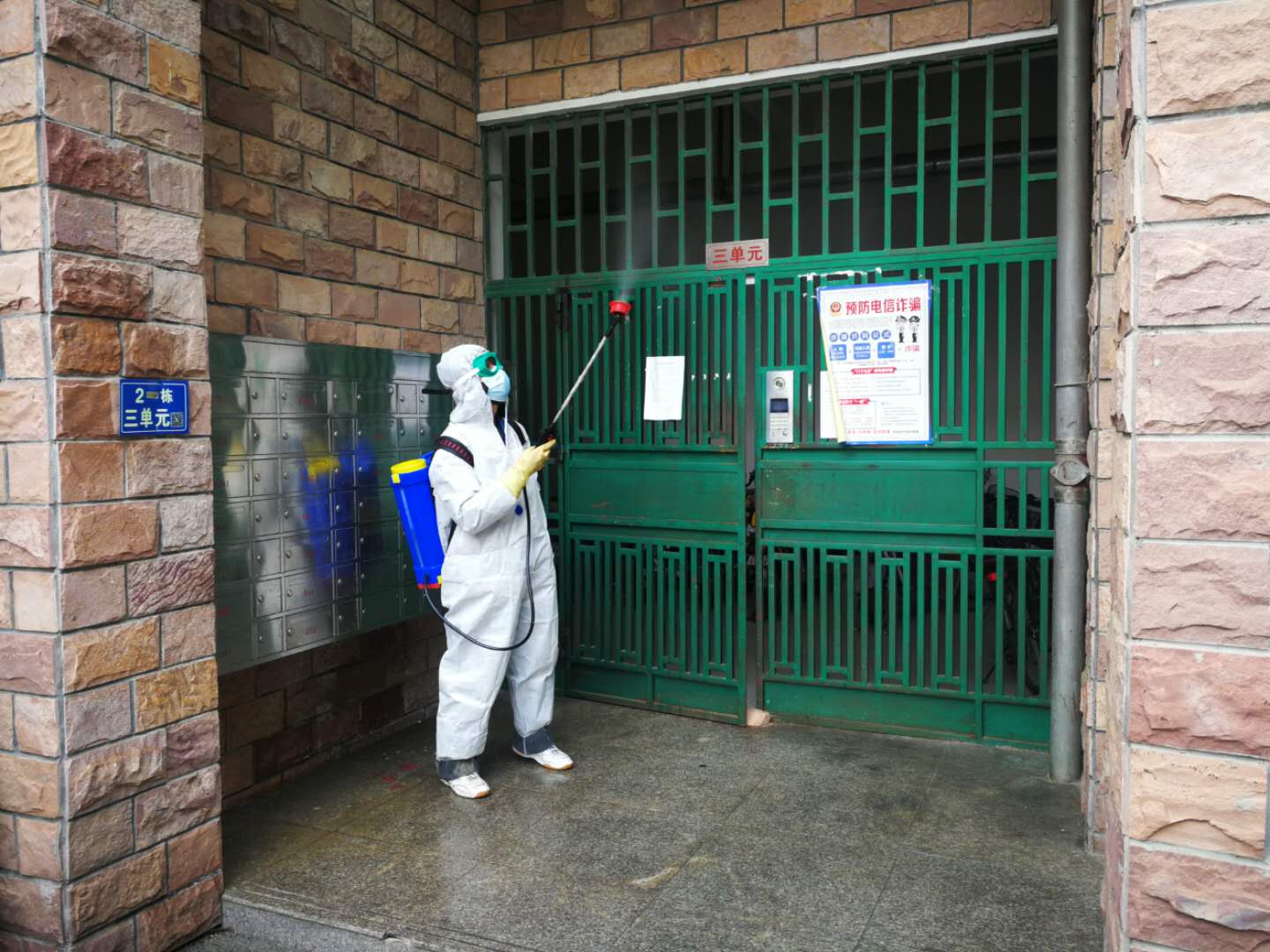

Many Chinese, especially the young generations, do not have much interaction with the residents’ committees in their daily lives. But under an emergency, you can see that the city couldn’t have made it through the crisis without them. Residents’ committee staff checked residents’ health and disinfected the neighborhoods every day, delivered food and medicine door to door, took out trash, and dealt with every emergency. Our study found that residents reported a significantly lower level of mental distress when the social infrastructure, both residents’ committees and volunteer groups, provided comprehensive services.

A residents' committee staff member disinfecting the building. Photo by Tang Ao.

Speaking of volunteer groups, how did they influence the neighborhoods during the lockdown?

As the pandemic progressed, residents’ committees were running out of capacity. So many residents volunteered to help their neighbors.

A delivery guy we interviewed impressed me a lot. He kept working during the lockdown. One day, he got an order with an extra 100 RMB tip to send meals to a hospital, the most high-risk area in the city where everyone avoided going. He found out that the order was from a lady who actually knew no one in that hospital and was moved by the news and decided to do something for the medical workers on the frontline.

The lady kept placing orders with tips from time to time. But one day, she gave him three N95 masks instead. He was very surprised and grateful to receive them because it was very hard to get even one. She told him that these masks were from a doctor to thank her for the meals. This frontline doctor wore the same mask for two days, but he still tried as best as he could to save masks for her. The lady decided to give them to the delivery man because she thought he needed them more than she did. He was so touched that everyone was caring about others although they were also facing risks themselves. To pass on this kindness, he decided to become a volunteer.

There were tens of thousands of volunteers like him who hesitated to volunteer at first but were motivated by the stories they read online, the help they received from neighbors and strangers, and the strong will they felt in people to defeat the virus. Even if many of them were under quarantine, they still worked on WeChat to comfort each other and coordinate whatever tasks were needed.

Helping others, in turn, cheered them up. I remember one volunteer told me “I would have been depressed if I had chosen to stay at home for over 70 days straight and do nothing.” The sense of belonging, connectedness, trust, and kindness they felt through the volunteer work proved to be effective in easing anxiety and building confidence.

Volunteers moving the donated goods. Photo by Tang Ao.

How can the findings be applied to other societies?

As mentioned earlier, China’s neighborhood’s organization structures are unique. Some activities that received positive feedback in China may not be applicable to other societies. But one thing for sure is that the strengthening in mutual communication and trust among residents - which is the social cohesion we stressed in the study - can lead to a more supportive and robust community united against a crisis. Governments can achieve this by constructing more opportunities for residents to build deeper relationships.

Our Center has just completed a similar study in Hong Kong and is collaborating with the NYU Sociology Department to collect data in American cities. We plan to compare the three sets of data to learn more about how different societies are fighting against the virus. This pandemic will not be the last public crisis for us. It’s always necessary to learn from experience and get better prepared for the next challenge.