The fourth grade students in the Pudong New Citizen Life Center are playing a guessing game. Their teacher, Isabel Brack ’22, writes the clues on a white board:

“MOUSE”

“WEBSITE”

“SOFTWARE”

A boy in a black jacket rings the bell on the desk. “COMPUTER!” he says.

His classmates applaud excitedly.

English word games are one way Brack brought the English language to life for her students at the community learning center some 13 km from the NYU Shanghai campus. As part of the Dean’s Service Scholars course, “ENGD-SHU 101B: Language & Power,” Brack spent 12 weeks last semester teaching English to the children of migrant workers. Taught by Co-Area Head of English for Academic Purposes and Senior Lecturer Steven Iams, “Language and Power” is a collaboration with the Shanghai NGO Stepping Stones China. Over two semesters, students studied linguistic and pedagogical theories and applied them to their classes with the children at the Pudong center.

Isabel Brack ’22 teaching Grade 4 students. Photo Credit: Stepping Stones China

The opportunity to learn about language pedagogy through course readings and seminar discussions and then to put theory into practice was invaluable, said Brack. “Many nuances to both the experience as a volunteer and a learner would go unnoticed if it was not for the combination [of service and academic instruction], and many important learning experiences would be lost.”

A cornerstone of students’ coursework are “dialogue journals,” a weekly reflective writing assignment that allows students to collaborate in pairs, writing an in-depth description of their class each week, including reflections on important classroom moments.

“The experience that students are having as teachers and the theories that we're talking about in the classroom overlap,” said Iams. “Students begin to see concepts such as translanguaging and linguistic imperialism in practice, and this awareness influences the decisions they make as language teachers. It is always very rewarding to see them put these pieces together.”

Cynthia Deng ’25 (standing in gray coat) and Genevieve Hendler ’22 (standing in white sweater) teaching on a typical teaching day. Photo Credit: Stepping Stones China

Social Science major Genevieve Hendler ’22 found that the teaching experience not only helped her identify “diverse nuances and unnoticed needs in the community," but also changed her attitude toward her own language divergences.

“As a trilingual, I was constantly frustrated by my ‘inadequacies’ in all three languages, and I never feel that I have conveyed my thoughts fully or that I have selected the best word,” Hendler said. While teaching, she noticed her students running into the same trouble in learning English as well, which made her realize that what she may think of as “mistakes,” “barriers,” or “holes” in language are arbitrary and unimportant if they don't truly hinder communication.

Every week, when she taught English classes at the Pudong New Citizen Life Center, Hendler made it a point to talk and joke with her students in both English and Chinese.

“Most people may have misunderstood the power of translanguaging and code-switching. After taking the course, I learned that allowing students to vocalize comfortably their needs and concerns helps the teacher understand what lesson topics to review or to emphasize.”

Humanities major Zhang Yihang ’24 said that “the usefulness of switching between two languages during the teaching” was his biggest takeaway. The Language & Power course was Zhang’s first opportunity to interact with migrant students, and he found that even in one classroom, there was a huge gap between students' English levels.

“Some students spoke very fluent English, while others could not recognize any English words at all,” Zhang said. The situation made him think constantly about how to make students feel comfortable in the classroom by using the languages they know to solve problems, ask questions, and ultimately learn new English words and phrases. “I never thought about such questions, but now, I realized that theories and practices are not universal, and you should always be prepared to be adaptable.”

Besides thinking critically about the relationship between theory and practice, Iams also encourages his students to ask themselves critical questions about the social and cultural context of language learning, comparing and contrasting their own language learning experiences and motivations with those of their young local students.

“My students need to go a step further and ask: Who is benefiting from learning English? Who can be an English teacher and why? What is the identity of their students? And why are these questions important to the way a class is designed and taught?” Iams said. “They have to dig deeply into the relationship between language and power.”

For Shanghai native Hua Yuxin ’24, this opened a new door for her. “Growing up in Shanghai, I’m used to taking language and language education for granted. However, this course makes me realize how the English language and its instruction are connected with socioeconomic status, geopolitical factors, and colonizing power,” she said.

Hua said she was shocked when she realized the unequal distribution of education resources in her own city, especially when she realized that her brother is about the same age as the kids she teaches, but he is at a much more advanced level in English. She realized that financially better-off people who reside in more developed regions have far better access to English education resources. Furthermore, when people think of a global language, they always first think of English, instead of Chinese and thousands of other existing languages. Hua said she could not help asking herself, “Why is it English?”

As Hua put it in a weekly dialogue journal, the relationship between language and power is “intricate and complicated, in that power determines who has access to what language, and who speaks the so-called ‘inferior’ language. Language serves as a social ladder to some and a stumbling block to others in the globalizing job market.”

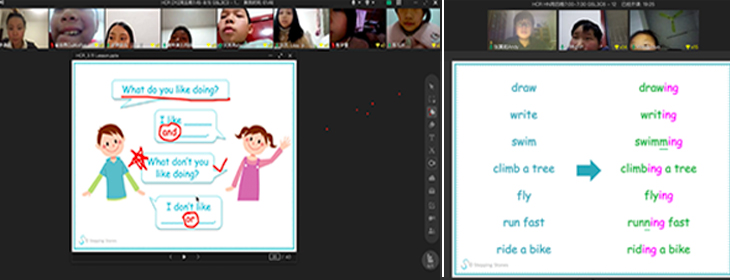

Due to the pandemic, Zhang Yihang ’24 and Hua Yuxin ’24 chose to teach online. “The difficulty for online teaching is the technical problems. Several students don’t have access to high-quality earphones, so the background sound in our class is always full of echoes and noises,” Zhang said.

After the fall semester’s training and practice, students have a chance to delve into the area that most interests them through the spring semester’s service project and independent research project. Some students helped to create and revise teaching materials, while others taught online via the Home Classroom Program linking teachers to classrooms in rural areas, and still others served as administrative coordinators for online teaching programs.

Students’ research projects examined a number of different applied linguistics and sociocultural language issues. Hua Yuxin chose to use language as a lens to reflect on privilege. Brack studied how the language level power dynamic changes across the age spectrum - from early childhood learning to geriatric memory care. Zhang Yihang dug into the linguistic implications of danmu online video comment systems.

Most participants said they believed the course was more than worthwhile as they watched their young students become more confident speaking English, and they themselves gained a more nuanced understanding of the limits and power of language learning. “You come out of the experience with more questions than answers, yet still a better understanding of the situation than before,” Hendler said.