It’s just after nine-thirty on a Monday morning, and bleary-eyed first-year students stream into the East Building, filling up the large auditorium, the only room on campus that can fit the more than 400 members of the Class of 2027. They’re here for Global Perspectives on Society, or GPS for short. Along with Calculus, it’s one of the only classes that every single student, no matter their major, must take in their first semester. First-years read texts, listen to lectures, and then discuss the readings in a smaller cohort led by a postdoctoral GPS fellow.

On this particular morning, Assistant Professor of Global China Studies Zhao Lu stands at the lectern discussing the week’s assigned text on the history of global science. His presentation is interactive and engaging, almost like a performance. He drops references in both Chinese and English to keep the students on their toes, and at one point he calls on them to critique images displayed on the screen. Between bursts of lecture, he shows short video clips from films and tv shows to illustrate his point about the role popular science has held in society. When he plays a video clip of Bill Nye the Science Guy or the popular Japanese anime show Cells at Work, laughs of recognition rise from students.

Then Associate Professor of Global Contemporary Media Anna Greenspan takes the floor. In her lecture, she discusses Chinese thinker Tan Sitong and the connections between scientific developments, national identity, modernity, and spiritual thought in China and the West. Her interest in the material is palpable. “Reading and thinking about ideas and understanding intellectual history and just thinking deeply about big issues is what life is for,” she explains later on. “I'm just trying to express some of that enthusiasm.” As she speaks, students straighten up in their chairs and furiously jot down notes to keep up with the pace of her lecture.

It’s like this every week in GPS. Professors Zhao and Greenspan take turns lecturing, introducing global thinkers from Confucius to Marx, connecting the readings with their own research, prompting the students with thought-provoking questions and bouncing off of each other’s perspectives. In their weekly recitations with post-doctoral fellows, students are asked to discuss the readings and make connections with their own lives. The course has taken on an importance of almost mammoth proportions for first-year students, who come from all over the world and from a diverse range of educational backgrounds. GPS confronts them with big ideas and a multi-layered way of engaging with them. For many, this is their introduction to a completely new way of learning.

So let’s go back to the beginning and ask a very GPS-like question: “How’d we get here?” To understand that, says Vice Chancellor Jeffrey Lehman, you have to go back even beyond the founding of the University. Establishing a core curriculum has been an important element of many great universities, as an attempt to guarantee that students gain a base of knowledge, usually centered around ‘great thinkers’ or ‘great books’ of the western tradition.

At NYU Shanghai, the creation of GPS as a core course arose from a different motivation, Lehman says. Instead of assigning a base of knowledge that all students would learn, GPS is about creating a unique intellectual community. “This would be a cohort-building experience and a broadening experience around this concept of being effective in a multicultural world,” he explains. GPS was designed to be a course that raises big, challenging questions, ones that don’t have single correct answers. “It was important that the reading materials and in-class experience be provocative,” he says. “But the main goal was to provide fuel for the conversation and discussion outside the classroom.”

Since the start, the course has always been taught by a pair of instructors, and that’s by design, say Associate Professor of History Duane Corpis and Associate Professor of Philosophy Brad Weslake, who taught GPS together for three years. Before them, Vice Chancellor Lehman taught the class for three years (one year with economist and Nobel laureate Paul Romer), and then again last year with Provost Joanna Waley-Cohen. Waley-Cohen says each GPS lecturer pair benefits by bringing the perspective of different disciplines. “[They are] great intellectuals and have a real commitment to building the intellectual community of the university,” she says.

Professor Weslake says that the approach is show rather than tell. “It's far more effective, I think, to actually show them what a conversation looks like when it's conducted in a rich and rigorous way,” he says. Team teaching facilitates that because the instructors model the process for the students during the lectures.

The course is always growing and changing. Along with the lecturing professors who set the syllabus, a team of postdoctoral fellows, under the coordination of Clinical Assistant Professor of History Erica Mukherjee, lead the weekly recitations, guiding students through the readings, sharing their own disciplinary perspectives and introducing supplementary materials for the students to discuss. These fellows help mold GPS into its unique, interdisciplinary form.

Professor Corpis describes the course as a process. “I never expected that at the end of 15 weeks, students will have mastered everything about these big world topics, social problems, political questions,” he says, “but rather that it gives them a foundation of tools, concepts, approaches, and also inspires them to ask further questions.”

Many students who enter GPS find it challenging and overwhelming to confront such a vast array of ideas, from Gilgamesh to Frankenstein, Plato to Lu Xun, and Laozi to Freud. Sang Rong ’17, who comes from a Chinese educational background, says she had a rocky start in the course when she was asked to critique a famous thinker’s work. “I was kind of shocked because they were authorities and how could I possibly disagree with them?” Later on, when the instructor explained that anyone could critique ideas because they were written in a certain time and context which could limit the writer’s thinking, Sang says she felt empowered to question and analyze the writings.

It’s not uncommon, say students, for ideas and thinkers presented in GPS to fuel spirited late-night conversations in the dorms. Pitchakorn Siripakorn ’25 says that concepts also resurface in other courses too. “It has broadened my awareness of the complexities that shape individuals and societies, encouraging me to approach challenges and opportunities with a more thoughtful and inclusive mindset.”

Sang says that even after graduating, she continues to utilize the skills she honed in GPS. Rather than suggest solutions, she says, “it cultivated our mindsets. We have formed our own way of thinking that helps us better understand the root of many issues in human society. When it comes to solutions, we can be more considerate and contemplative.”

That’s important, Professors Greenspan and Zhao say, because university offers this unique time in students' lives where they can begin to grapple with big, sometimes contentious ideas and learn how to work together. “I don't want to be too grandiose about it, but I think it's so critical at this difficult moment that we're in,” Greenspan says. It is even more unique that they are doing so in Shanghai, where old and new, east and west, collide. In the weekly recitations, international and Chinese students engage with each other in debate, sometimes heatedly, over topics as varied as how we live in communities, the role of the state in our lives and predicting the future. “[It] demonstrates that we could bring people together,” says Zhao. “While they have huge differences, we could build something and solve problems together.”

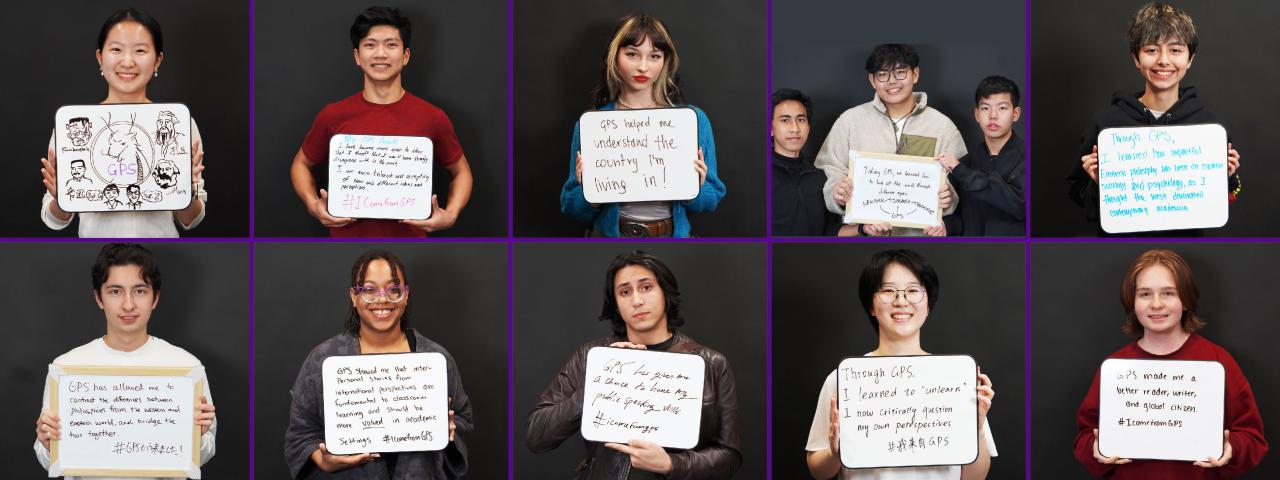

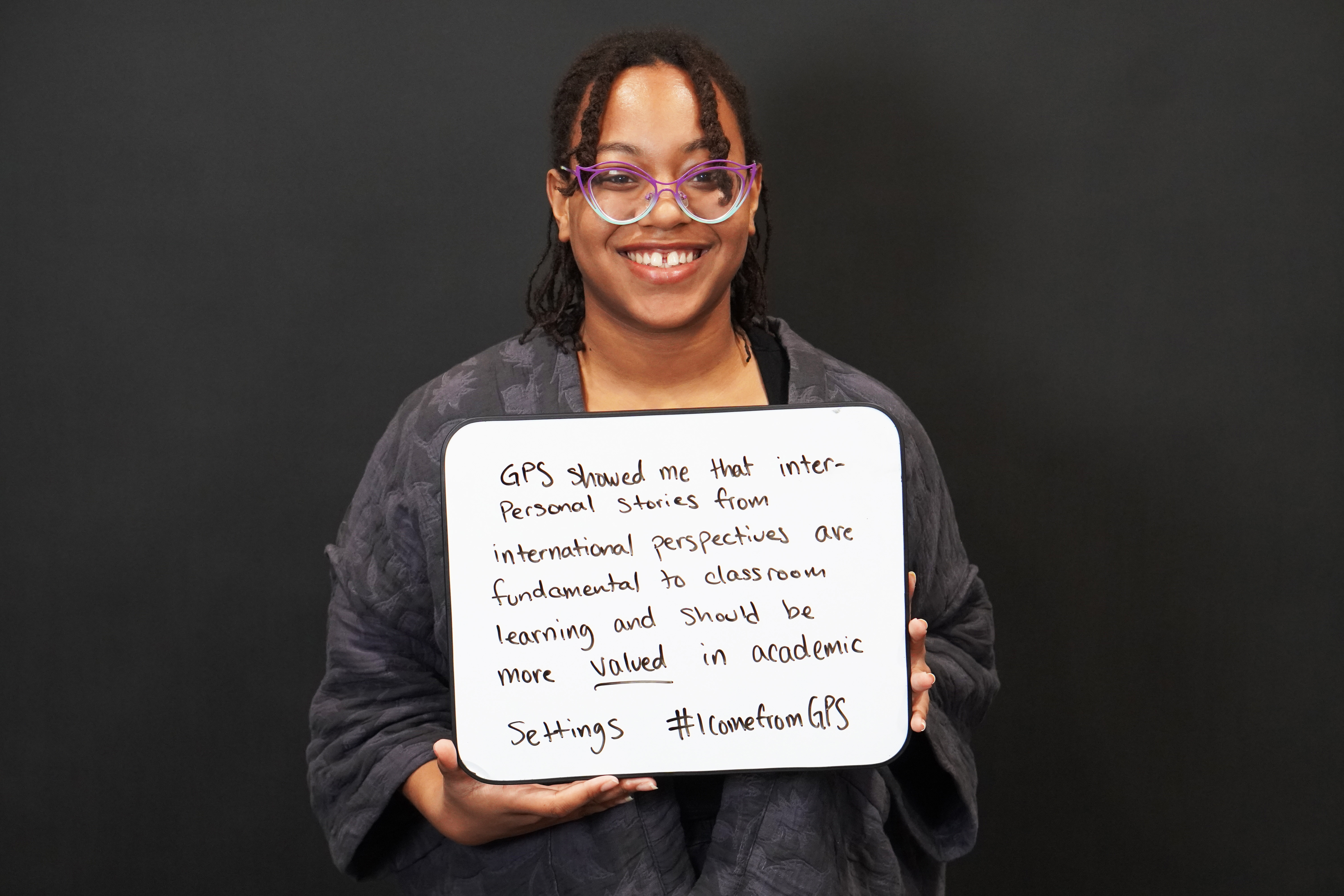

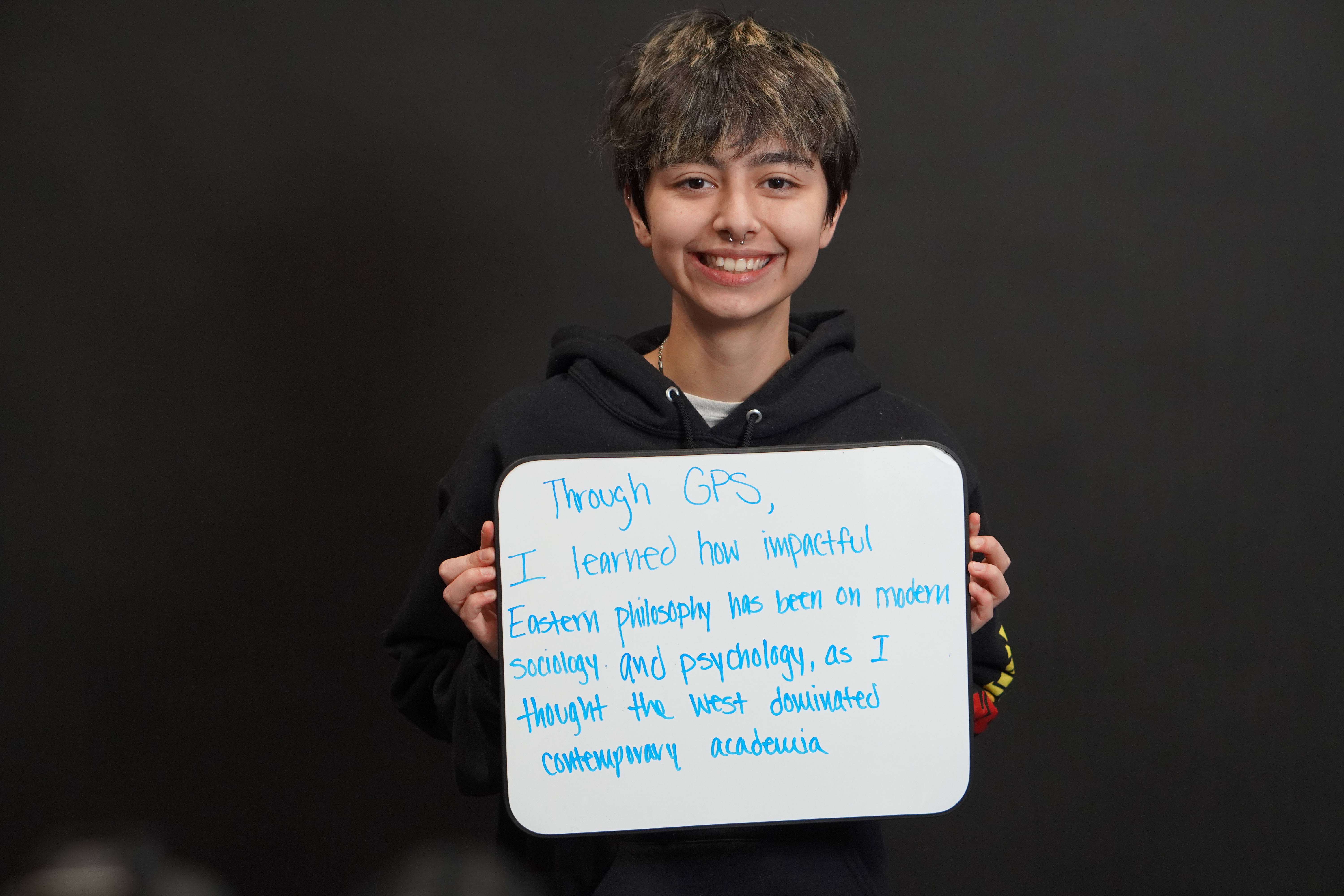

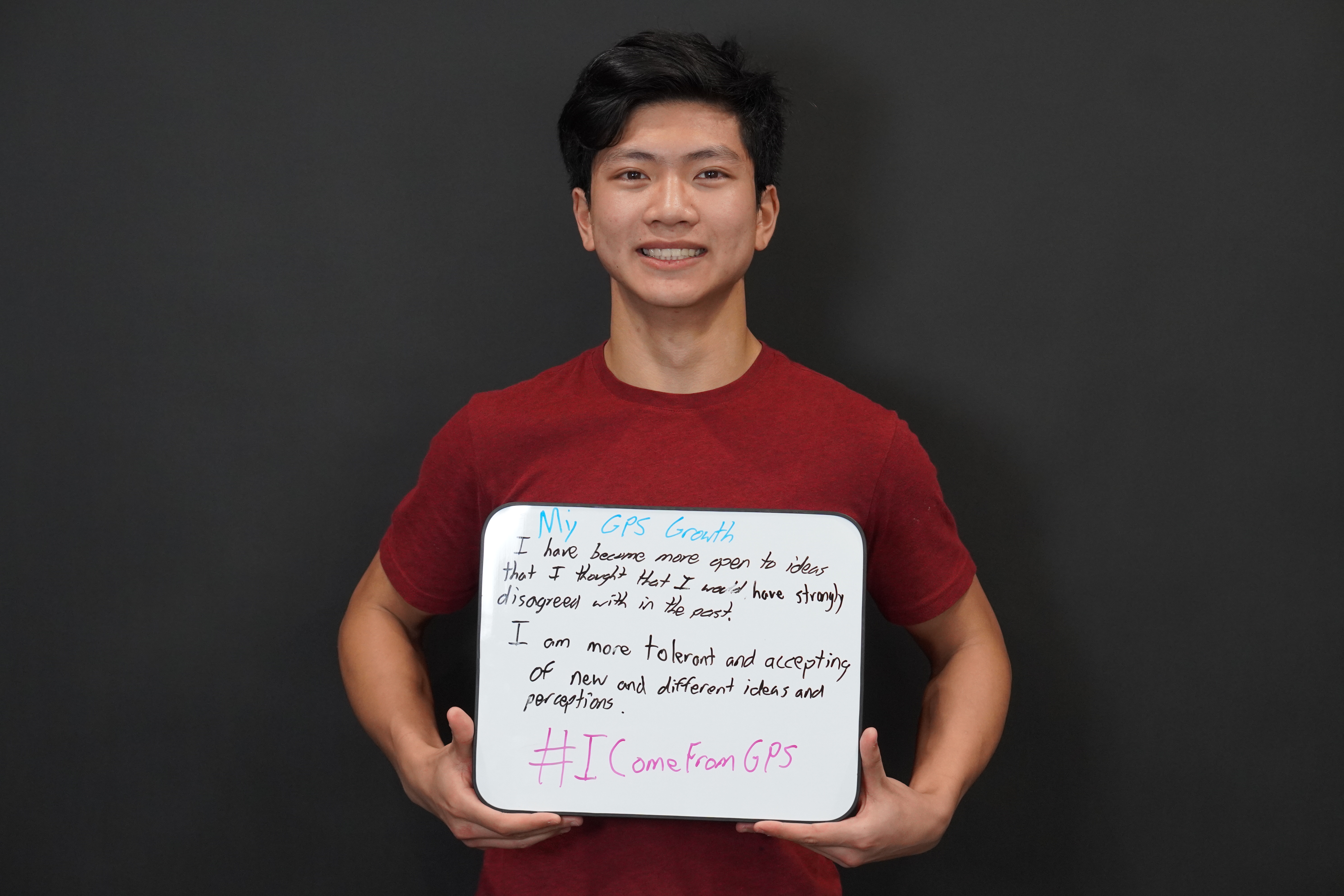

Photos taken by Postdoctoral Teaching Fellow for GPS Dr. Warren A. Stanislaus as part of his #icomefromgps #我来自gps digital media project, which explores the impact of GPS through the eyes of over 70 students from the Class of 2027.