100-year-old Holocaust survivor Ruth Sherman this week shared the story of how Shanghai saved her and her family’s life with NYU Shanghai students in Associate Professor of History and European Studies Alexander Geppert’s course, “Europe’s Long Twentieth Century,” which examines the social, political and cultural history of Europe from the late nineteenth to the early twenty-first century.

Sherman was one of 20,000 European Jewish refugees who arrived in Shanghai in the late 1930s and early 1940s, fleeing Adolf Hitler’s Nazi regime. As a girl in Berlin, Sherman saw Hitler twice in parades in the city’s streets, each time running away before others in the crowd could force her to salute him. In an interview from her home in Burbank, California, the centenarian answered students’ questions about her flight from Berlin and her family, friendships, and everyday life as a teenage refugee in China from 1939 to 1947.

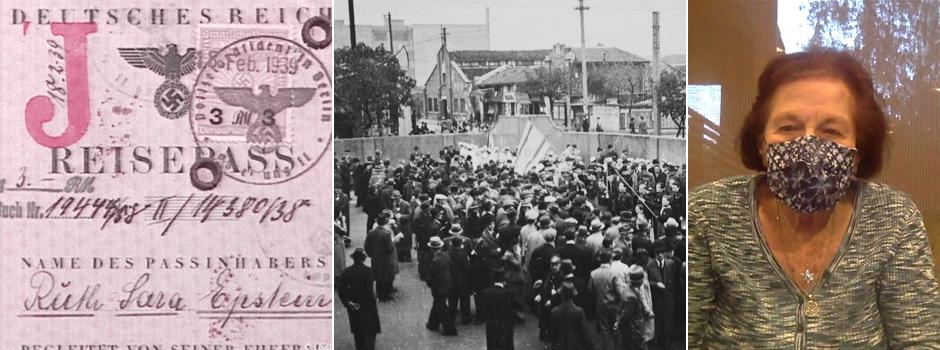

Life in the Chaoufoong “Camp” in Shanghai’s Hongkou District (known to Sherman and her fellow refugees as Hongkew) was starkly different from the life of modern comfort that many contemporary Shanghai residents enjoy. The then 18-year-old Sherman and her 13-year-old sister had no choice but to live in a separate building from their parents, who in turn shared one dormitory-style room with six other refugee couples. Their camp had no running water, no heating, and no kitchen – her mother had to improvise a small charcoal stove from a flowerpot, where for eight years they cooked beans and rice, often the only food they could afford.

“It was a pretty hard time,” Sherman said. “[But] we were very happy and grateful to China that they let us in there and we survived, because all my relatives [who remained in Europe] were killed.”

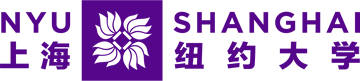

Title photos: Left: Sherman’s German passport, stamped with a giant red “J” to identify her as a Jew. Center: A Zionist rally in Shanghai in the mid-1940s. Right: Ruth Sherman in November 2020, at 100 years old.

On the left, young Ruth (seated) talks with her mother Lucie Epstein as she puts on makeup in her parents’ dormitory room in the Chaoufoong Camp (pictured at right). This and other photos of Sherman’s time in Shanghai are part of the Shoah Foundation’s 1995 interview with Sherman, which can be viewed in its entirety here.

On the left, young Ruth (seated) talks with her mother Lucie Epstein as she puts on makeup in her parents’ dormitory room in the Chaoufoong Camp (pictured at right). This and other photos of Sherman’s time in Shanghai are part of the Shoah Foundation’s 1995 interview with Sherman, which can be viewed in its entirety here.

But Sherman also enjoyed hanging out with her friends in the camp, watching other refugees playing baseball in the camp’s yard, making music together, or enjoying plays staged by refugees at a local community hall. She had a part-time job, fixing collars and buttonholes at a small dressmaker’s shop owned by a fellow refugee. When her future husband had a little extra spending money, they would go on group dates to the Mascot Hotel’s rooftop garden, or to the department stores on Nanking (now Nanjing) Road.

“The most intriguing part of Mrs. Sherman's experience in the 1930s and 1940s to me is actually how similar our experiences were as a teenager,” said Meredith Lu Ruiqi ’24 of Hohhot, Inner Mongolia. “I couldn't relate more when she talked about how she would talk back to her mother, saying ‘I just want to do this’ when her mother asked her to do a particular thing, or hearing about how it was forbidden for a boy and a girl to hang out on their own.”

“Her answers helped me realize that history is not only words written down on pages, but was once an actual life someone used to live.”

Sherman speaks with students in Shanghai, the United States, and Vietnam via video from her home in Burbank, California.

Sherman speaks with students in Shanghai, the United States, and Vietnam via video from her home in Burbank, California.

“Once students talk to somebody who has been through that, I think it changes their perspective completely, because suddenly there's some history to almost touch,” said Geppert, who became acquainted with Sherman by chance through family in the United States. “Maybe they will learn that things are much more simple, but also much more complex than what they have learned in class.”

The part of Hongkou where Sherman resided later became the Japanese administered ghetto for “stateless refugees” – primarily Jews from what was then Nazi territory – from 1943 to 1945. Though many historical sources have emphasized the brutally restrictive policies the Japanese imposed on ghetto residents, Sherman reported that residents of her camp did not feel such intense restrictions, since most of their movement was controlled by a “police” force comprised of fellow refugee camp residents. Lu and several of her classmates, including Marcus Zha Yuhong ’24 of Hangzhou, Zhejiang, said they found this detail surprising.

“During her life in the ghetto, she seemed to have nothing to do with the ongoing war at all,” said Zha. “She said that she saw ‘the Japanese hit the Chinese a lot,’ while the Jewish people were relatively well protected. It shows the complicated interests and relations behind the war.”

Geppert says such unexpected contradictions illustrate one of the class’s key themes about the complexity of intercultural relations between Europe and other regions.

“She takes her Jewish German culture, attitudes, and worldview with her and her family wherever she goes. She tries to adapt, but then she moves on to the US, so she shows how these linkages between Europe and China - Europe and Shanghai - happen through individual lives.”

Only around 400,000 of the Holocaust’s 3.5 million survivors (the last of a pre-war European Jewish population that was nearly 10 million strong) are still alive today, and that number shrinks daily as more and more survivors pass away. That makes opportunities to talk directly with people like Sherman all the more imperative now, says Geppert.

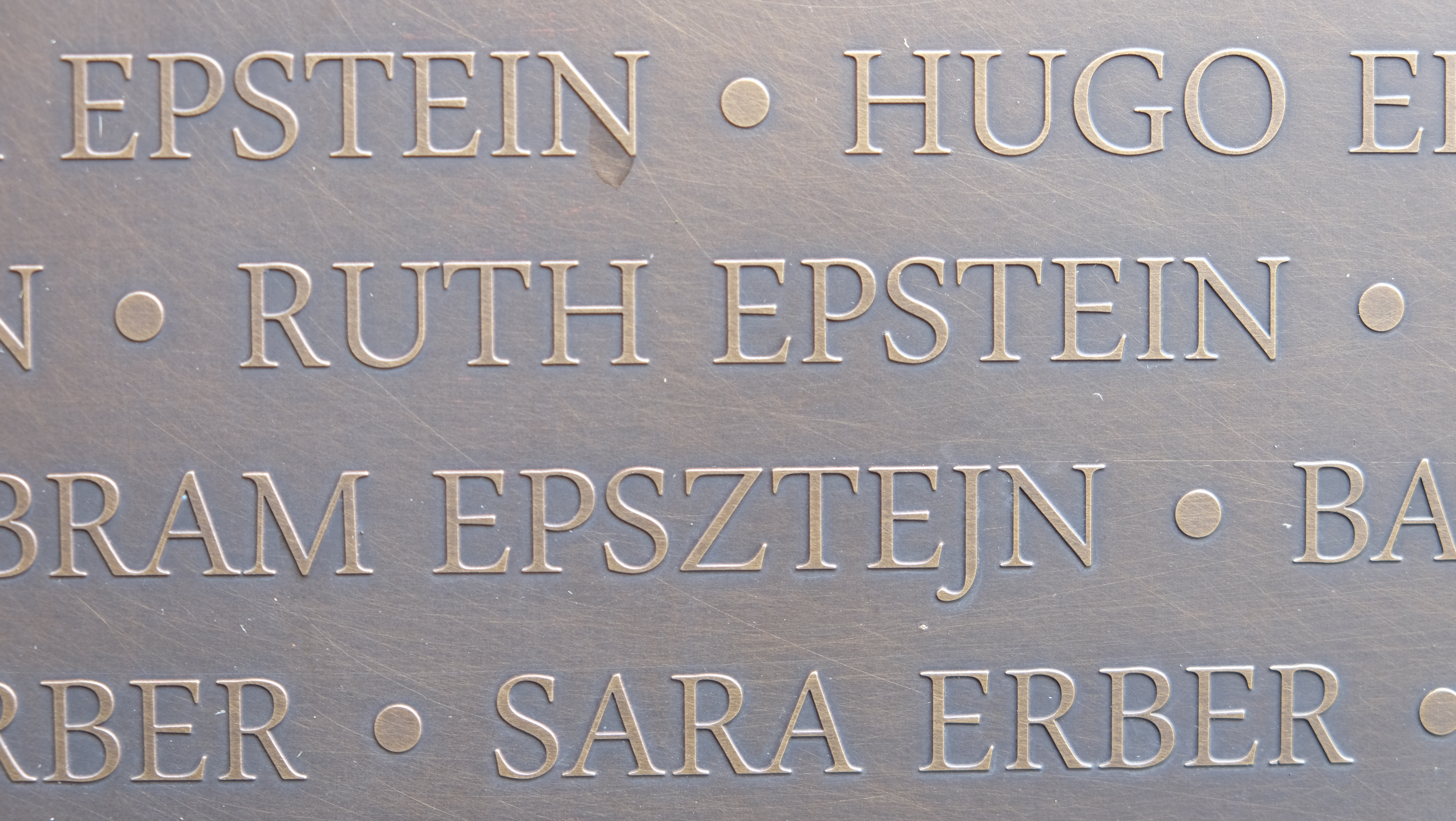

The memorial wall at the Shanghai Jewish Refugee Museum lists Sherman under her maiden name, Ruth Epstein, among the names of roughly 20,000 other European Jews who sought refuge in Shanghai from persecution and mass murder in their home countries. Photo by Alexander Geppert.

“Hearing how many members of her family were killed, even the ones that moved to other places in Europe, definitely made the death toll of the Holocaust much more real,” said Caleb Dawson ’24, who joined the interview from his home in the United States via Zoom.

“Talking with Mrs. Sherman made me realize that I am very grateful for the circumstances under which I am going to Shanghai. In these times of coronavirus restrictions, it's very good to remember that I am moving to another country by choice, not out of desperation for my life,” Dawson said.

Zha said talking with Sherman made him view his own role in Shanghai differently as well. “Mrs. Sherman’s experience shows us that, in this international community, we should treat everyone who comes from different regions equally with respect. Every nation’s people all will or have already suffered some disasters, but the humanity of love and unity have always existed, and people from different nations will all come together to face the same evil. Humans are kind and good-natured, … and we shouldn't have prejudice due to historical reasons.”

Special thanks to Rebecca Gotlieb and David Sherman for facilitating Ruth Sherman’s interview with Professor Geppert’s students.