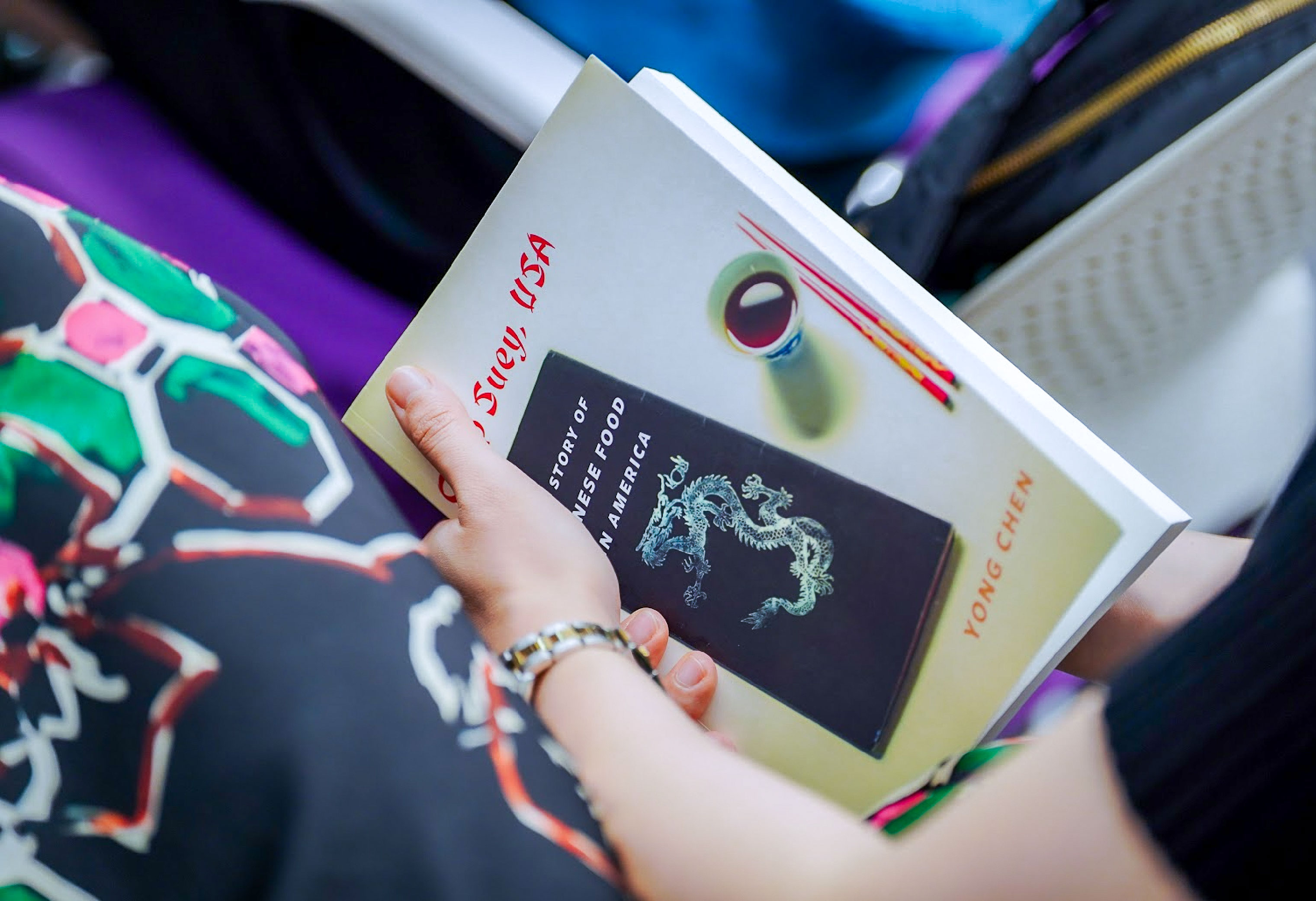

What makes something authentic? That’s the question this year’s NYU Shanghai Reads program asked with the selection of Chop Suey, USA: The Story of Chinese Food in America by Yong Chen as their campus-wide reading selection.

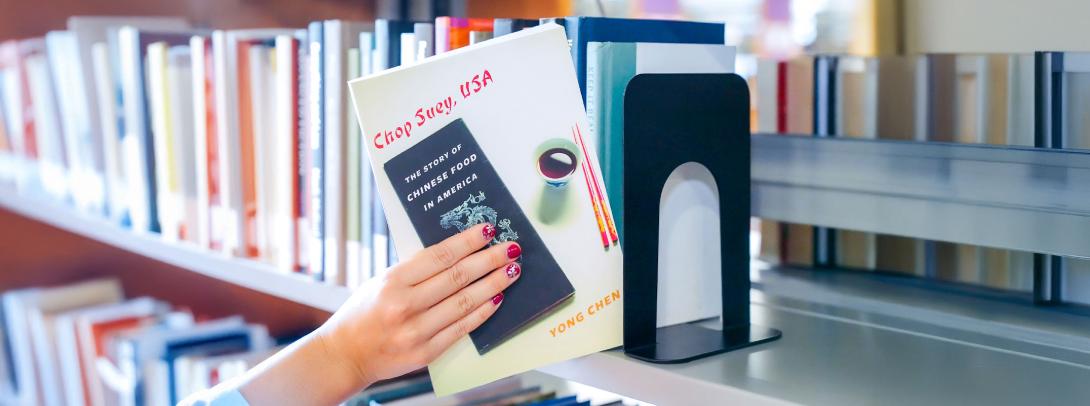

On September 25, students, faculty, and staff gathered to discuss the book and the theme of authenticity in an event facilitated by Global China Studies Assistant Professor Ka Lee Wong.

NYU Shanghai Reads is NYU Shanghai’s annual community reading initiative, which invites the campus community, from first-year students to faculty members, to engage in dialogue around a single text chosen to spark intercultural understanding. While the book serves as a shared theme during first-year orientation, the broader community continues the conversation throughout the academic year through lectures, workshops, and cultural events.

Yong Chen’s Chop Suey, USA examines how Chinese-American food evolved from a marginalized cuisine to a defining feature of America’s dining landscape. By following the rise of dishes like chop suey — a hybrid creation widely thought to be “invented” in America — Chen reveals how Chinese immigrants navigated racism, exclusion, and economic hardship through culinary innovation.

“This topic moves beyond a single culture,” Wong said. “It exposes a universal process — how people use food to negotiate belonging and difference wherever cultures meet.”

“We wanted to explore the diversity of migrant cultures, which speaks to most students here,” Professor Wong explained. “The book uses the story of Chinese-American food — a cuisine born from partnership and exchange — to explore how cultures adapt and build something new together. That mirrors the very spirit of NYU Shanghai itself.”

NYU Shanghai Reads co-chair and Director of Academic Resources Jin Tong said she hopes the book selection will inspire the NYU Shanghai community to engage in meaningful conversations and learn from one another. “Chop Suey, USA invites us to see food not just as something we eat, but as a powerful way to connect cultures, histories, and identities,” she said. During the discussion, participants analyzed the meaning beneath Chen’s question: Is chop suey “real” Chinese food?

“It’s less about whether it’s ‘real’ and more about who gets to decide what ‘real’ means,” Wong argued. “Chop suey was a survival strategy that became a cultural symbol — one that speaks to the creativity and resilience of immigrant communities.”

For Joshua Wong ’26, a Business and Finance major from New York City, the discussion topic touched on something deeply personal.

“In recent decades, racism no longer dictates public attitudes towards Chinese food the way it once did,” he reflected. “But negative perceptions, including old stereotypes, have persisted.” He cited how Chinatown restaurants are often described as “cheap eats,” unintentionally reinforcing class-based stereotypes. “It’s complex — because many Chinese immigrants really did rely on restaurant work to survive — but the framing can feel exploitative,” he said.

Benjamin Cheung ’26, who grew up Asian-American in New York City and now studies Computer Science at NYU Shanghai, said the event served as an opportunity to see how food reflects generational change.

“I’ve always seen the story of Chinese food mirror the story of our community,” he said. “Older generations built their lives in takeout restaurants but pushed their children toward ‘upward mobility.’ Yet, Chinese food keeps evolving — from Cantonese and Toisanese roots to new regional styles, and even global names like Din Tai Fung.”

That evolution, students agreed, challenges any fixed idea of “authenticity.”

Mattis Nurit ’26, a Global China Studies and Social Science double major, said he joined the session to better understand how Chen redefines authenticity in the context of diaspora.

“What struck me most is how the idea of authenticity depends on perspective,” he said. “Food isn’t fixed — it’s a negotiation between memory, place, and adaptation.”

Nurit added that hearing the perspectives of students who grew up in China added nuance to his understanding. “Food can be both familiar and foreign depending on where you stand,” he said.

Zhang Yuchen ’27, a Humanities major from Shanghai who said she’d never heard of chop suey before reading the book, discovered that dish’s meaning in English and Chinese couldn’t be more different.

“I looked it up and found it translated to 杂碎 [zasui meaning offal] in Mandarin — which I only knew as a northern slang word. It surprised me to learn it was once the most famous Chinese-American dish.”

Zhang, who lived near Manhattan’s Chinatown during her study away at NYU, reflected on the irony of never seeing the dish on menus there. “It’s fascinating how Chinese food developed its own features in the U.S. out of the restaurant owners’ need to survive,” she said. “They adjusted to American tastes — and in doing so, created something entirely new.”

For Professor Wong, those cross-cultural discoveries are exactly what the NYU Shanghai Reads program is designed to inspire.

“Food is one of the most universal languages we have,” she said. “By examining something as familiar as chop suey, students begin to see how migration, adaptation, and identity are deeply interconnected. It’s not just a national story — it’s a human one.”

NYU Shanghai Reads will continue exploring the intersection of food, culture, and identity through a series of themed events throughout the semester. Upcoming sessions include “Building an NYU Shanghai Recipe Book: How We Cook Home When We’re Away” (October 21) by Instructional Services Librarian Vanessa Lawrence and Digital Scholarship Librarian, Luo Fan, and "Rooting in the Soil: How to Build a Community through Food?" by Dr. Tianyun Hua (November 11) which will invite participants to reflect on how food shapes memory and belonging across borders.

Students said they are eager to keep the dialogue going — not just about food, but about what it represents.

“It’s not just about cuisine,” Joshua Wong said. “It’s about how communities survive, how they adapt, and how they turn something humble into something lasting.”

That’s what it comes down to– cooking may happen in the kitchen, but its meanings transcend far beyond the dinner table — connecting people, histories, and identities across continents.