Student: Chen Xinyue ‘22

Faculty: Professor Keith Ross, dean of computer science and engineering

Before coming to NYU Shanghai, computer science major Xinyue Chen ’22 didn’t have a background in programming or coding. But by the end of her freshman year, the Shanghai native had completed Machine Learning, a highly-competitive course taught to upper class students by Keith Ross, dean of computer science and engineering. After diving into a Dean’s Undergraduate Research Fund (DURF) project with Ross and a team of three other classmates and two PhD students -- Chen has spent over the past 10 months deep in collaborative research--programming, coding, and conducting simulated robotic experiments.

Learning linear algebra over winter break

Xinyue Chen: I took Introduction to Computer Programming in my first semester out of curiosity. I put a lot of effort into it and found that maybe I was good at coding; it felt easy to me. In the second semester of my freshman year, I decided to challenge myself to try a more advanced computer science course--I wanted to take Professor Ross' Machine Learning course. My advisor and friends weren’t very encouraging, but at the time, I was feeling brave.

Keith Ross: Xinyue was a freshman in my Machine Learning class when most students are taking it their senior year. She is a very serious student, really hardworking, and very passionate about research and her work.

Xinyue: I knew it would be a challenge for me because I still needed to learn linear algebra, so in the winter break before that spring semester, I got a linear algebra textbook and I taught myself. In just the first few weeks of taking Machine Learning, I already had a ton of questions for Professor Ross. One of them was: are there any research opportunities in your group? He was encouraging and gave me, as a freshman, the opportunity to participate in his DURF group.

Developing algorithms over a summer DURF project

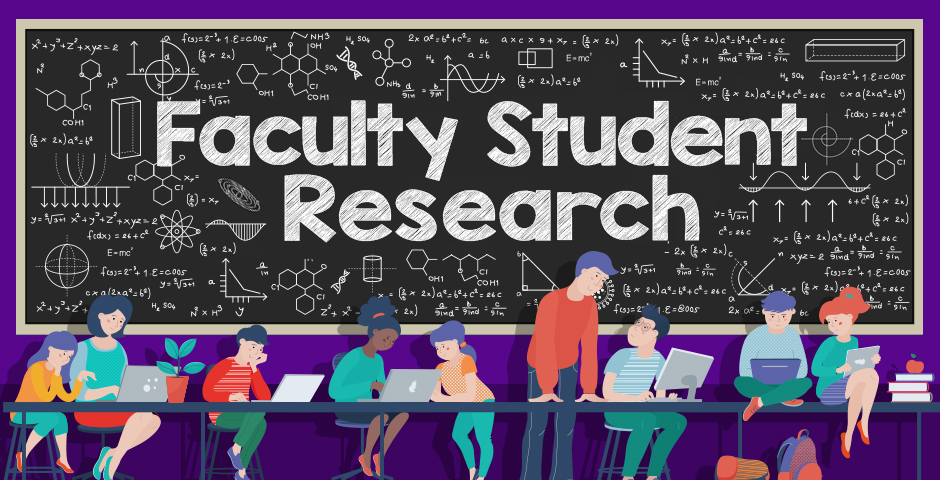

Keith: Our current research project stems from what we started last summer, working on a DURF project. The area we’re working in is a sub-branch of artificial intelligence called deep reinforcement learning. It’s actually equal to two sub-disciplines that are married together: deep learning--a really hot topic powering the hype of AI with major breakthroughs like facial recognition, natural language processing, translation, self-driving cars, object recognition (so the self-driving cars don't run into trees)--plus reinforcement learning, another topic in AI. The application area we're looking at is applying deep reinforcement learning to robotics, but we don't have a physical robot -- we use simulated robots in our experiments.

Xinyue: We spent the first half of the summer learning about the subject material and over the second half of the summer we started doing research, running experiments, and writing code.

Keith: The goal is to train the computer-simulated robot to do various tasks, like running. We come up with different algorithms, different approaches based on deep reinforcement learning, to try to solve these benchmarks, to get the robots to learn quickly.

Xinyue: First we have an idea of the algorithm then implement it in code. The first stage is testing our idea to see if the code would work in our simulation environments. We coded some algorithms according to our idea, tested it on the environment, and it nearly completely failed. When you do any experiment, you will for sure meet multiple failures. We tried hard to find out why we failed and then modified the algorithm.

Image from the Poster,: “Best Action Imitation Learning in DRL” by Xinyue Chen ’22 and Zijian Zhou’20. A MuJoCo (Multi-Joint dynamics with Contact) environment where algorithms are used to demonstrate continuous tasks such as walking or running.

Training robots to run faster

Keith: There are several research teams we are competing with that are using the same set of benchmarks--a big team at Berkeley, teams at Google, too. It’s tough because they’re very strong teams. So what these research teams try to do is try to get this guy to learn as quickly as possible using different algorithms. That's kind of an idea of what we're trying to do. Initially, the robot isn’t even standing properly. You have to put forces on it. It has many different joints on his body and you apply different forces to different parts of his body and hopefully he'll start to run. The algorithm doesn't know anything about anything at all. The only thing it knows is how fast he's running or maybe if he's standing too. The algorithm just knows that it can do different things and it gets some kind of reward.

Xinyue: If the robot runs at a high speed, we consider this good, so we give it a higher reward. If it's running slowly, we give it a lower reward. If it's not completely running, or isn’t learning how to run, we give it a very low reward. The reward reflects how the agent is doing with the task, so this is how deep reinforcement learning algorithms can be generalized.

Keith: This is this reinforcement learning idea: the algorithm just tries out different things and over time it starts to learn what the right thing is.

Xinyue: I was fortunate that at the time with my experiments, I found that one version of my algorithm could work well and had potential. Professor Ross was very encouraging on this. He said, “Oh I think this has potential, we should continue to work on this,” so we took some extra time after the DURF project, got separate results, and have continued to work on this until now.

Xinyue Chen '22 working individually on her research

A balance of individual and teamwork

Keith: There are six of us working on this one project right now. Xinyue, another guy, Zhou Zijian ’20, who is a senior computer science and honors math double major, along with two of my PhD students and a third undergraduate honors math major based in New York. Things slowed down during the fall because the students have courses, but we worked again over the J-term here.

Xinyue: I recall in the summer, we would meet at least two or three days a week. We would meet all together in a conference room on campus to talk about if we had any progress with our algorithms, discussing if we were going to switch or pursue a specific direction.

Keith: We’d meet and then break up, and the students coded and ran experiments. We used the high-performance computing system very extensively here, and the undergraduates ran experiments on that--and they’d write programs and show the results and we’d discuss and modify the algorithm.

Xinyue: We’d have very active discussions each time we met. We would meet for at least one hour--sometimes up to three hours or so. For example, we’d meet at 10 AM and sometimes the discussion would last until 1 PM, and when we all got to the school's cafeteria, there would be hardly any lunch left.

Keith: They talk among each other and they come and talk with me privately. 80% of the time they're coding and running experiments by themselves, but 20% of the time they’re meeting and discussing. We send emails to each other; we even have a WeChat group. They do most of it when courses are not in progress.

Xinyue: We have a good atmosphere in Professor Ross’ group. Sometimes he would ask us to do a presentation to see how well we understand a specific text or concept, and with the encouragement of the others, I was able to better my presentation skills. I really appreciate everyone in the group, especially two of his Computer Science PhD students, Wang Che ’17 and Wu Yanqiu ’17, who work with us and have been very kind by assisting those of us who started from scratch with zero DURF experience.

Keith: The advantage of undergraduate students doing research at NYU Shanghai is that it’s a smaller place -- it's easier to get to know your professors and the classes are smaller compared to NYU in New York. It gives the students a greater opportunity to get to know the faculty and get involved with faculty and research.

Xinyue: I think it's special that NYU Shanghai provides such an opportunity for undergraduate research, and I think Professor Ross is very open-minded. He always says we should not hesitate to make any suggestions or say ‘Professor you are wrong about this specific idea.’ I think each of our group members have the experience of challenging him. And he’s happy if we challenge him--whether we are right or wrong.

Keith: They're not just doing what I tell them; they have their own ideas, and they don't hesitate to express their ideas, and they don't hesitate to disagree with me sometimes. So all of that is good. We have a very nice dynamic. The students are trained to be critical thinkers, and they are critical thinkers, and it works out in a very positive way.