NYU Shanghai Professor of Physics and Mathematics Jun Zhang is the Co-Director of the NYU-ECNU Institute of Physics. He’s also someone who thinks deeply about the connections between art and science. Here he talks about how those connections have carried him along a winding academic and personal path.

Let's go back all the way back to the beginning of your academic journey.

When I was much younger, I was into fine arts for some time. Even after I got my bachelor degrees in physics, I worked as a freelance illustrator for two years. It was fun, but then I needed to advance my degree for physics.

Your life has taken some interesting twists and turns. How do you navigate those times when things go off course?

I see myself as Tom Hanks in the movie Forrest Gump. Life can be incidental. I've been driven by incidents, occasions. But at the same time, you need to be persistent. It's both—you persist, but you shouldn't be too persistent. You kind of adapt to your environment.

I went to Israel for my PhD study in 1989 and then a year and a half later, the first Gulf War started. It was a very tense situation—gas masks were distributed to dormitories. I went to Denmark for a visit. I visited a group there and found what they studied was quite interesting so I changed my field from optics to fluid physics. Then I transferred universities and I graduated with a PhD in physics from the University of Copenhagen. Both places are exciting, but very different styles. During those days as a student, I was quickly able to see some of the forefront of research.

After that, I went to New York for my postdoc at Rockefeller. I applied for a postdoc with a very well-known scientist. Initially, he rejected me, but soon I found we had a lot in common about art. And he also discovered that I practice fine art on the side. Just overnight, he switched his decision.

What were those years in New York like?

The city inspired my research, I think. In an exciting place, you want to do exciting things. I often feel like it's my second hometown.

It's a meeting spot. It's a mixing pot. You see so many different people from so many different countries. Because it's a mess, it's exciting. And you are immediately a New Yorker the day you arrive. Once you are there, you immediately have a sense of belonging. I don't think any other city in the world has that.

Life might throw you opportunities, might throw you challenges, but you just sort of have to keep going.

You continued to move between fields.

I started at Rockefeller to do biophysics. That's totally different from what I had been doing up to that point. While working on biophysics, my interest in fluid physics was still going strong.

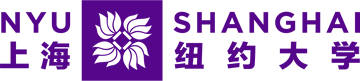

So I came back to fluid, something that combines rationality, but also a visual perspective. It has the element of art—you can present in many different ways. And not just the equation, logic or diagram—it's much richer than that. This field is very classical, but at the same time a modern science. It bridges fundamental science and applications, and many different mentalities.

What kind of personality do you want your science to carry?

If possible, I want my science to carry humanity and perhaps art in some way. I try to bridge disciplines in that regard. I don't want to frame myself within a limited boundary. For me, it's natural, because I’ve sort of been on both sides. I hope I can have a balanced view of what I see, how I perceive things.

What are those connections between art and science?

I think that depends on the person. When you see things, when you discover things, you actually discover yourself. Nature is a mirror, it reflects who you are. Through fluid physics or fluid dynamics, you see what you want to see. The topics you select are certainly the reflections of your value and taste.

It's like going to an exhibition. When you look at a piece of art, it's up to you to take what you want to take [out of it]. It's like a piece of music. There's no written law that says you better enjoy this piece of music in a particular way.

In science, it's similar. But you better appreciate the rational side, and then you convince your colleagues that this opens up new doors to future research. You have to do this part, otherwise you don't get things published, especially to top tier journals. For that, you have to be extremely rigorous.

But on the other hand, there's still a lot of room for you to put your own personality in, [for example], how you present the work, how you visually display your results. There’s a lot of room to be yourself.

Does that influence how you think about your own research?

I have been trying to do "simple physics". I have a belief that when your science is simple, it's more important and fundamental. If it’s too complicated or too technical, the big picture is often gone.

What is driving you to sort of reach outside of your sphere to bring this perspective to other people, for example with the Art of Science exhibition (at NYU Shanghai)?

I think maybe this comes from my understanding about art and science. These two should not be distinguished too much. They're quite close and they are connected internally through us. Richard Feynman once said scientists are looking at beauty in different ways, but we appreciate beauty even deeper.

Do you still engage in artistic practice yourself?

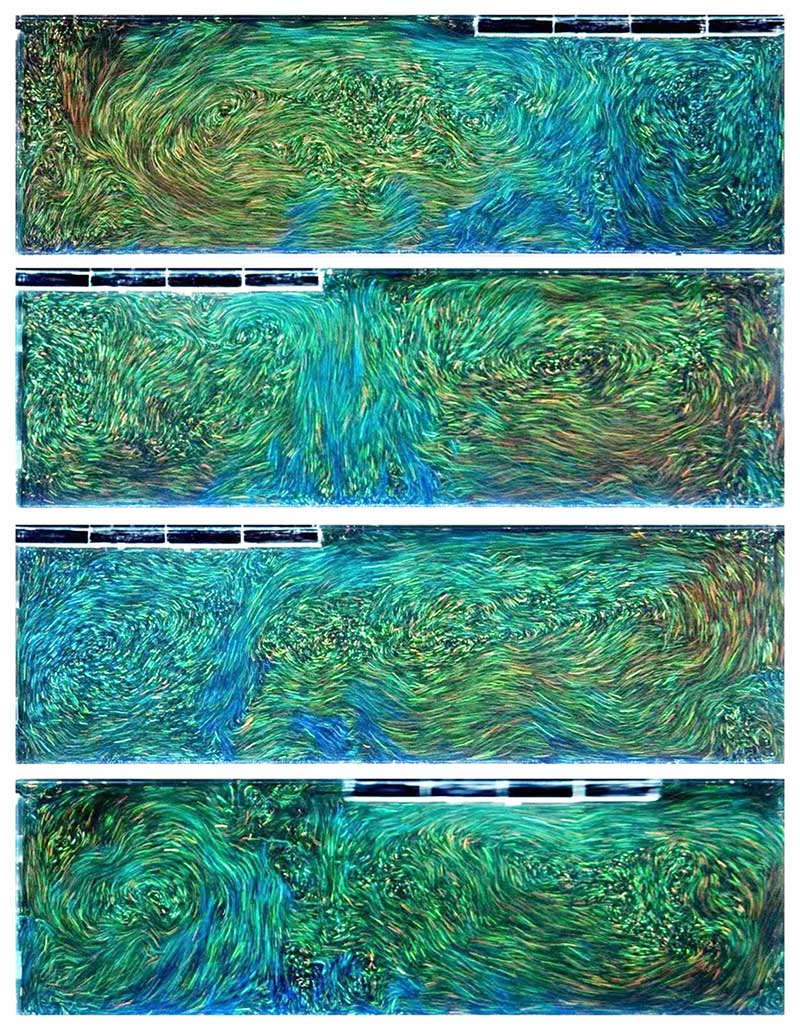

Yes, I do. I usually carry a sketchbook whenever I go out for sightseeing or to a city that I have never been to. If time allows, I might take a short walk somewhere and do a sketch for my own record.

What is it about that practice that helps you to experience or enjoy a place?

Maybe the other part of myself emerges. I want to keep a record of it, put a little marker in my journey. That's kind of a compulsive behavior, if you like, not a bad one.

When you draw, it's a remarkable experience. I think everybody should do this. I still recall the moment when I did a drawing, even [it was] 20 years ago. The smell, the atmosphere, the heat, the sunlight—it's all there. It's very vivid. 20 minutes, 30 minutes, in the field, in the Arctic Circle and in Antarctica. If you ask me to recall, I think I remember most of the details. It’s not that I have a good memory, it’s just because at that time, I don't know, something magic happened.

Did being honored with membership in Academia Europaea have any impact on your future research?

It's a recognition from others. I appreciate it. You show your work, people recognize it. Will that influence me in any way? I think no, not really.

The research itself is already so rewarding. We have a playground to do things we enjoy, over which we connect to the most bright and interesting scientists all over the world. At the same time, we can have a very intimate dialogue with nature. We corner the other part to answer our curious questions, to fulfill our curiosity. Every now and then we get a definitive answer. That's a huge reward better than anything.

So if it isn’t recognition, then what is pulling you forward?

The answer may be a little boring, but it's true. It's the next project, always the next question. I'm blessed with curiosity. I'm curious to know so many things. I’m curious about people, how nature works. As you can see, most of my works are inspired by natural phenomena. Nothing is more satisfying than explaining nature.

You were saying being in New York inspired your research. Has Shanghai inspired you?

Working half time at NYU Shanghai is similar. In Shanghai you go out, you interact with the local people. And then you learn what life is. That’s part of the curiosity, part of the learning.

Very often, the human tendency is to stay in their comfort zones, but a new place forces you to get out of this comfort zone to explore, to go beyond. So in that regard, it is very healthy for someone's career, for someone's brain, and probably for someone's health as well [to teach and work in a new place].

I think I’m lucky to have had that several times. Some people might see it negatively [but] I liked my Forrest Gump experience.